| Homepage |

| New books |

| News in Brief |

| list of late magazines |

| Articles Recommended |

Articles Recommended |

|

|

AN ANTELOPE OF FASHION

George B. Schaller

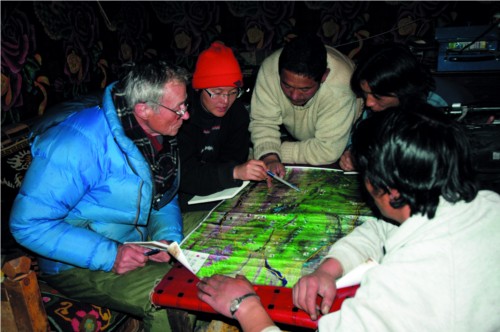

Research fellows at the Pamirs. Photo by Xi Zhilong

Tibetan antelopes.

Over a decade ago, I gave a talk about Tibet and its wildlife at a luncheon of fashionable guests in New York, hoping to raise funds for further cooperative conservation projects in China. I showed photographs of the beautiful Tibetan antelope, also known as chiru, tsi, or zangling yang. Large herds migrated in my photographs, mothers suckled their young, and males with long, slender horns traversed the treeless Chang Tang uplands. Then I showed camps of poachers with stacks of naked chiru carcasses with hides removed. Chiru have the finest wool in the world. Smuggled to Kashmir in India, the wool is there woven into shawls, marketed as shahtoosh, meaning king of wool in Persian. When I mentioned shahtoosh, several women quietly slipped shawls off their shoulders. They had not realized that each of them had in effect draped themselves with the bodies of three to five dead chiru. They only knew that a shawl is extraordinarily soft, a symbol of fashion, and expensive, a lovely embroidered one selling for as much as $15000.

I first encountered chiru during a wildlife survey in Qinghai in 1985. At that time, I was only aware that they lived on the high Tibetan Plateau, most of them between 4300-5000m in elevation and that they were confined to China, except for a few that strayed into India. Travelers in the early 1900s had seen the animals in vast numbers with "15000 to 20000 visible at one time", to quote one report. There must have been well over a million animals at that time. No one knows how many chiru there were in the past or how many exist today. At their low point in the 1990, my guess was that possibly fewer than 100,000 remained. As our recent surveys suggest, they have surely increased in recent years.

George B. Schaller and baby antelope. Photo by Cai Xinwu

I was intrigued by the chiru, as well as by wild yak, kiang or Tibetan wild ass, and Tibetan gazelle who also share the chiru's austere habitat. After that first visit, I returned again and again to the Chang Tang to study the chiru with coworkers from the forestry departments of Tibet, Xinjiang and Qinghai, as well as the Plateau Institute of Biology and Peking University. To unravel the intricacies of the chirus complex life as they wander endlessly beneath the great sky filled with light and silence, was a challenge, and so was the need to protect this unique species.

By traveling cross-country and recording where chiru are, the direction of their movements, the size and composition of their herds, and other information, we soon learned that some chiru are resident, remaining relatively local, and that some are migratory. The migratory populations spend the winter in the southern Chang Tang where grazing is good and where they share pastures with nomads and their livestock. They migrate north in spring where females gather to calve in specific but barren areas. There are, as far as we now know, five such migratory populations. One, for example, travels north into Xinjiang from Tibet and another turns from Tibet northeast into the Hol Xil area of Qinghai. Among migratory hoofed animals, chiru are unusual in that only the females migrate far. The males do not join the females on the calving ground, and, in general, move relatively little. Why do females migrate as far as 250 km to have their calves in late June and early July, then immediately start on the return journey? They expend so much valuable energy especially then pregnant and lactating.

We wanted to find out why chiru migrated from fine grasslands to desolate terrain to calve. We followed herds as they urgently hurried north along well-defined routes. Yet we failed several times to reach the mysterious sites where they gathered. Once in the west, beyond the Aru basin, the chiru moved beyond our reach into Xinjiang; Another time, in Qinghai's Hol Xil, it snowed so much and then melted that all our vehicles bogged down in the sodden, sandy soil.

Liu Yanling and Dr. Kang Aili are working on a high-tech instrument.

Finally, in 2005, we reached a calving ground by crossing the Kunlun Mountains from the north. With Kang Aili of the wildlife Conservation Society, Liu Yanling of Peking University, and a local staff we entered high rolling hills and lake basins, uninhabited and desolate. Scatted low shrubs and patches of coarse, sharp-tipped sedge were the main patches of coarse. June 18 we spot the first newborn, a small tan lump curled up in the open. It looked so lonely in this vast, wild emptiness. Kang Aili slowly approached it and picked it up. We weigh it: a male, 3.5kg. Then we gently replaced it and retreated. We found many young on the following days. A newborn can rise and stumble after its mother within 15 minutes after birth, stay close to her because she is always on the move. Indeed, during the first week of July, before the birth season is over, some females already begin their southward migration to the winter range. Not all females have a newborn at heel. A few have been killed by red fox, wolf, and golden eagle, and some died during days when snow storms and icy winds lashed the landscape. So why do chiru calve in such desolation? I still don't know. Perhaps they need a place where predators are few and people absent--perhaps they need peace above all.

We obtained valuable information during this study. But even more important, the prefecture declared the area a reserve, the West Kunlun Nature Reserve. It is contiguous with Tibet's Chang Tang Reserve. Now this chiru population can continue its annual trek within protected areas. In addition, we helped to establish a guard post near the calving grounds to prevent poaching.

Dr. George B. Schaller and Dr. Kang Aili with locals.

Back on their winter range, the chiru congregate at certain places in late November for the rut. The males are magnificent, fashionably adorned with a black face and black along the front of the legs, contrasting with their almost white coat. Vigorously they try to gather females, roaring and running around with head lowered and ail raised. If a female in near, a male may strutt beside her, muzzle raised, making himself look impressive. Sitting among the chiru and watching their sacred annual ritural of renewal, my mind was focused only on such a glorious moment, not on their uncertain fate.

Initially my interest was on the life of chiru. But in the late 1980s an ominous new problem began, that of a mass-slaughter of chiru. According to government figures, 20,000 animals a year were killed, probably a low estimate. Motorized teams of poachers from such cities as Xining gunned down females as they gave birth. The famous Qinghai anti-poaching team, named the Wild Yak Brigade, led by Suonan Dajie, intercepted a truck with 600 chiru hides, and in Xinjiang similar arrest were made. In 1992 alone an estimated 2000 kg of illegal wood reached India. At first I had no idea for what the wool was used, but then I discovered that the chiru died solely to satisfy a fashion craze for shahtoosh.

Fortunately anti-poaching efforts by China has greatly reduced the killing. International enforcement against the illegal trade-200 shahtoosh shawls were seized in one raid in London-and publicity also had an impact. Chiru have even become a mascot of the 2008 Olympics. But chiru poaching continues, though at a much lower level. Some Tibetans even use motorcycles to chase chiru until they collapse, exhausted, and can easily be slaughtered.

Much of the chirus range now lies within protected areas, a great achievement by China. In November 2006, I observed chiru along the Golmud-Lhasa highway. The animals showed little concern for the heavy traffic, indicating that they felt relatively safe there. The railroad was built with concern for wildlife, and chiru readily pass back and forth through the many underpasses.

On trip in November and December 2006, I joined a team that crossed the northern Chang Tang west to east. Led by Danda of the Forest Police in Tibet and Tashi Dorjie Hashi in Qinghai, we drove in two trucks and two Land Cruisers for 3000 km across the Chang Tang, Hol Xil, and Sangjiang Yuan reserves to Maduo County. About half that distance was in roadless uninhabited desert steppe, bleak and partially snow-covered at 5000m. Because Karma Khampa had organized the expedition so well, we had no hardships even though temperatures often dropped below -25?? . Cang Jue Drolma, Wang Hao, Kang Aili and I wanted to census wildlife over a route taken only before, in 1896. There were to my surprise quite a few chiru, over 8000 along over route in the uninhabited part both males and females.

I wondered if many females failed to migrate south as usual because of so much human disturbance there. Males are not in that area during summer. So from where did they come to join the females for the rut?? This trip revealed that our knowledge of chiru needs to be much improved if we are to protect and manage them effectively.

My visits to the Chang Tang have shown that nothing remains static: Wildlife numbers change, cultures change, ideas and policies change. I remember Pujong Narla, a nomadic herdsman. When I met him and his family in 1991, they lived in tents and rode horses to herd livestock. When I made a return visit in 2003, Pujong had prospered. He had three huts in various places of his rangeland, motorcycles, and a truck. With a change in government policy, Pujong and others received a private plot of land within which they have to keep their livestock. Much of the rangeland is being fenced. Will livestock now overgraze the fenced pastures? Will the fences keep chiru, kiang, and others from migrating? Will Pujong tolerate competition for grazing from wildlife on his pastures? Conservation must continually adapt to changing circumstances.

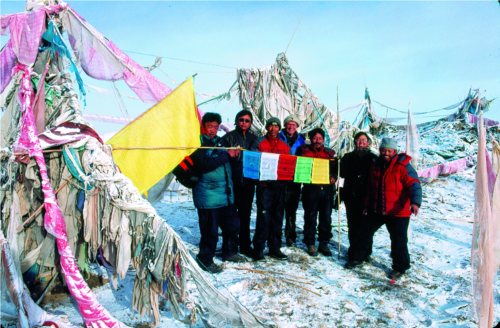

Research fellows at Hoh Xil.

Conservation ultimately depends on the hearts and minds of the local communities. The pastoralists of Cuochi village in Qinghai provide a wonderful example. On its own initiative, the village has set aside land for chiru and wild yak where was livestock grazing has been prohibited. In addition, sacred mountain Morwudan Zha protects the animals and plants there. All hunting in the community is forbidden and local teams monitor wildlife to assure its safety. Religious cognition and ecological insight have made the community understand that their future, their livelihood, depends on treating the rangelands and all its beings with respect, care and compassion. They have heeded the words of saint Milarepa:

But help living beings

Because that is truly pious work.

In such concern by communities lies the hope of a golden future for the chiru, one of China's precious treasures.